By John Devine

Special to Ontario Construction Report

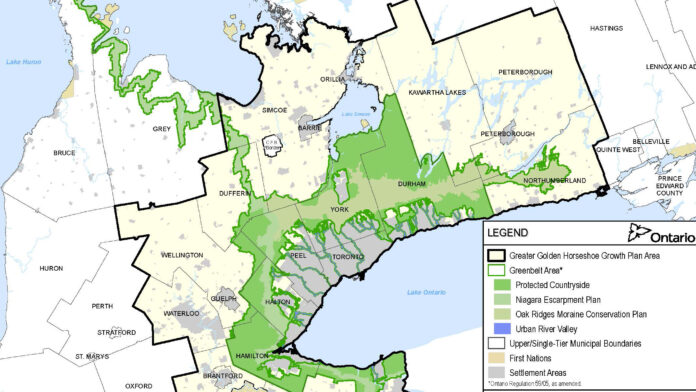

When Ontario’s development plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) region first arrived back in 2005 it was heralded by developers, municipalities, and environmentalists as a blueprint for creating sustainable complete communities for the 21st century.

The Places to Grow act aimed to direct growth to the region’s urban centres, with density and employment targets for 2041, since updated to 2051. Farmland and green spaces were to be protected as urban centres grew into places to live, work, and play … in other words, complete communities.

Now, however, with changes to the original plan and the increasing use of Ministerial Zoning Orders (MZOs)s to fast-track projects, that original shared vision is fraying, according to one leading environmentalist.

“The Places to Grow act, when it was first built, was a really good template to create communities of the 21st century that are thinking about financial and environmental sustainability, and adapting to a changing climate,” Margaret Prophet, executive director of the Simcoe County Greenbelt Coalition, told the Ontario Construction Report.

“The changes that have happened since then have continually weakened the original plan, basically encouraging sprawl.”

Most recent changes introduced last summer included revising the planning horizon for reaching density and employment targets from 2041 to ten years after. That, and others, caught the attention of environmentalists like Prophet, who is quick to say she is not anti-development, but prefers the approach first articulated in the growth plan.

“Places to Grow as originally designed was supposed to direct development to areas that were already serviced, so that you could realize cost-savings and invest in community versus having pay for additional infrastructure,” she said.

“There was a servicing hierarchy. The old Places to Grow said growth must go to a place that is either serviced or is feasibly serviced … it had to be on municipal water and wastewater. And then, if you couldn’t possible do that, we would consider private or communal, but those were not really accepted … because they failed so often and were costly.”

The servicing hierarchy, continues Prophet, got changed along with the planning horizon, to allow housing to be built in areas that weren’t already serviced, a tweak she says that allows sprawl to occur.

“That allows mega-development projects to go into places that they really shouldn’t be allowed, because now you can put them on communal servicing. Having to put development where existing water and wastewater exists just naturally determines where growth can go. Changing that servicing hierarchy means that now you can put it wherever you want.”

Complete communities, as envisioned, include services and amenities, and without the servicing hierarchy “it’s really difficult to build communities that are equitable, climate friendly, and economically sustainable,” says Prophet.

The current approach to growth seems to be at odds with Places to Grow’s original vision of directing development to the GGH’s urban centres. Those communities are planning for population and employment targets, and now finding themselves in completion with rural regions on their boundaries, says Prophet.

Barrie, for instance, is working towards a population of 298,000 by 2051, and 129,000 new jobs to support the growth. Immediately to its south in Innisfil The Orbit project could bring as many as 150,000 to the shores of Lake Simcoe over the coming decades, and to the north of the city in Springwater Township a development is underway to add 2,500 houses to the area.

“What is the long-term thinking? Will Innisfil be able to attract that number of people, and what does it mean for Barrie when you have a city just to the south of it?”

Directing growth to Barrie is not a new idea. Back in 2006, the Inter-Governmental Action Plan for the County of Simcoe, Barrie, and Orillia (both of which are separated communities from the county structure, dealt with growth. In the report, in which the Province was also involved, the future of Simcoe County was considered, with Queen’s Park suggesting the report’s direction align with Places to Grow vision of growth in urban centres, like Barrie.

Questions of safeguarding the region’s water resources were considered, says Prophet. The vision encountered regional pushback. “That was 2006, and here we are 15 years later.”

The Innisfil project is the subject of an MZO, one of about 20 centred on developments proposed for the county, says Prophet. Environmentalists and others decry the use of MZOs for circumventing the normal planning process, fast-tracking proposals. She also wonders how such a large development can be compatible with the Lake Simcoe Protection Plan, the Province’s approach to protecting the ecological health of Lake Simcoe and its watershed.

Goals of the plan include:

- promoting immediate action to address threats to the ecosystem, such as excessive phosphorus

• targeting new and emerging causes of stress such as invasive species and climate change

• protecting and restoring important natural areas such as shorelines and wetlands

• restoring the health of the fish and other aquatic life

“So, we have a government that is supposedly very committed to Lake Simcoe, and while they haven’t ruled on it yet, is entertaining a proposal to put in 150,000 people in the middle of farm fields.”

For its part, the Township says additional studies will “help to ensure that there are no negative impacts on Lake Simcoe and its watershed.”

Communities across the GGH region are facing the same growth-related issues, says Prophet, brought on by the changes to Places to Grow and the increasing use of MZOs. One of the groups in which she is involved, yourstoprotect.ca, maintains what she calls an “issues map” on MZOs and their impact.

“We are seeing MZOs being applied for in the Greenbelt and new highways that have development approval proposals attached to them. All of those little details (changes to Places to Grow) that seem not so important … those are the things that get put into the formulas that determine how much land gets taken up and where growth goes.”